MARK 'COACH' MINEART

Sabbatical 2022

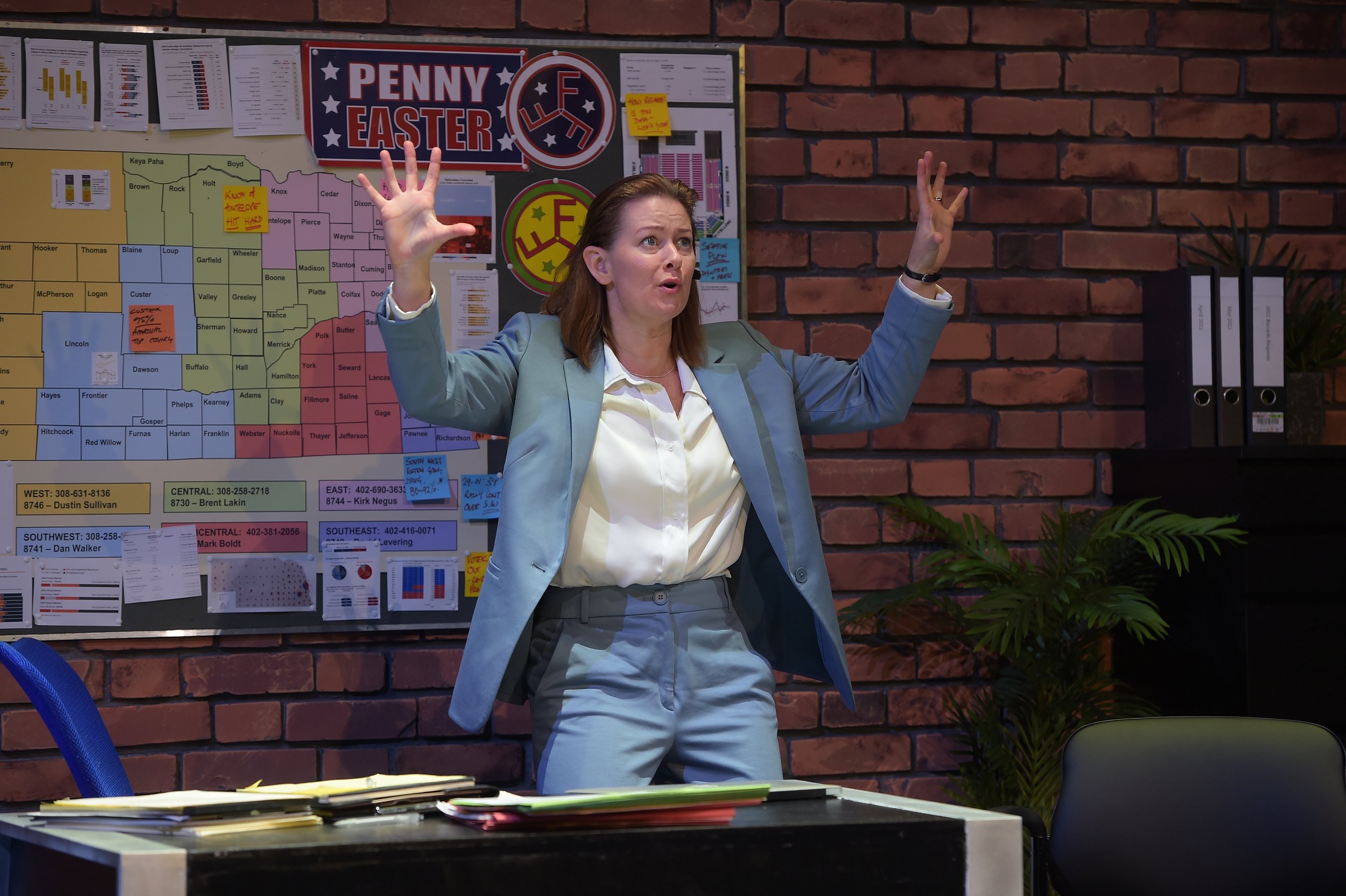

The Totalitarians, English Theatre Frankfurt

Mark Mineart

Otterbein University, Department of Theatre & Dance, Fall 2022 Sabbatical Report

SABBATICAL ABSTRACT:

I conceived and directed the European premiere of The Totalitarians by Peter Sinn Nachtrieb at the invitation of English Theatre Frankfurt.

The Venue:

English Theatre Frankfurt (ETF) is Europe’s largest English-speaking theatre. ETF produces an annual season of 4-6 productions consisting of plays and musicals, using exclusively native English-speaking performers and directors, chiefly from the United Kingdom, occasionally, the United States.

The Job Description:

As director, there are literally a thousand decisions to be taken on any play in every area of production before it gets anywhere near the rehearsal hall. Each of these decision contributes directly to what audiences will experience when the curtain rises: how the play is read, examined, developing the framework for how to approach the manifestation of the play based upon the text, but equally importantly, taking into account the given circumstances of the community within, and for, which the production is being produced. The director collaborates with the producing theatre on the scope of production, why that particular play was chosen, how it fits into the overall artistic and business goals of the producing theatre’s season, working with the casting director on what each role demands so they can bring in the most appropriate and wide section of actors for consideration, reviewing auditions selecting actors, creating the world of the play through collaborations with scenic, props, costume, lighting, sound, and video/sfx designers, and working with stage managers and the production manager as how rehearsals are to be structured, etc.

Once those tasks are completed, there are then several thousand more decisions that must be taken once rehearsals and builds actually begin: staging the play, exploring character relationships, working comic timing, choreographing stage combat & intimacy, coaching dialect work, discovering the optimal way in which to work with the performers, both individually and as a company, in order to help them bring forth their very best work for the benefit of audiences. Throughout the process of performance rehearsals the physical build of the production is continuing.

The director has thousands of decisions to make during the build in every area of technical production as opportunities /problems are found and as breakdowns inevitably occur. All of this is concurrent with rehearsals.

Once the build is complete, the set successfully loaded in, and the play fully staged and the actors’ performances orchestrated, it is time to bring together the work and talents of every area of production (performance, sets, props, lights, costumes, sound, video/ sfx, stage management) and fitting them together. This stage of production is called tech, and yes, there are again, thousands of decisions to be made by the director during this critical stage of production.

After technicals come dress rehearsals. Here the decisions to be made are polishing adjustments based upon the dress responses. These adjustments deal mostly with issues of timing: performances, scenic shifts, light cues, sound cues and volume, etc.

Then comes the hardest part of the director’s job: sitting in the house on opening night waiting to see what all of those many thousands of decisions will bear.

DESCRIPTION OF RESULTS/HOW THE GOALS WERE MET

Goal 1: Successfully direct the European premiere of Peter Sinn Nachtrieb’s The Totalitarians for the English Theatre Frankfurt. ‘Successfully’ in this usage encompass: getting the show cast, designed, rehearsed, built, and opened: being well-received by audiences, garnering favorable press, as well as being commercially beneficial for the producing organization (English Theatre Frankfurt).

Metrics for Success:

• Self-assessment

• Feedback/Reporting by ETF Artistic/Production heads and staff • Audience Reception and Press

• Peer Review

Self Assessment:

The English Theatre Frankfurt’s production of Peter Sinn Nachtrieb’s The Totalitarians started pre-production March 2022, began rehearsals May 12, 2022, premiered June 18, 2022, and had its final performance July 24, 2022.

The Totalitarians had 33 performances and was, through the lens of business concerns, a clear success. The production me English Theatre Frankfurt’s projected audience numbers and revenue goals as reported to me by Igor Trkulja, ETF Director of Marketing and Graphic Design.

The realization of The Totalitarians as a finished piece of work performed for the benefit of live audiences was also objectively successful. It produced good to excellent results in the areas by which most, if not all, mainstream theatre performance works are measured: it was was a commercial success for ETF as the producing organization, universally well received by the press, enjoyed by audiences (audience responses are document later on), and well commented upon by peers, as well as by colleagues.

Examining the entire process and results of The Totalitarians from the standpoint of a working theatre professional in a highly competitive and oversaturated field, the project was highly challenging, as well as highly successful, beneficial, and satisfying. The addition of a political satire to my directing resume further demonstrates my capacity to work across a wide scope of disparate material, and the fact of it being a European premier grants an additional level of weight to the accomplishment. I have deepened my relationship and portfolio of demonstrated abilities with the major English speaking theatre in Europe. This success, and my prior record of good work with the company, should recommend me for future opportunities with ETF.

The success of The Totalitarians has also raised my professional profile within my circle of acquaintance both nationally and internationally, as well as led to brand new relationships. I have created new professional relationships with Marc Frankum, the theatre’s UK based casting director, as well as Richard Evans, the production scenic and costume designer. These relationships open up potential avenues of collaboration internationally beyond ETF.

As an educator responsible for the training of future theatre professionals, in addition to the experiential knowledge I have gained and am currently synthesizing and have already begun bringing into my classes and rehearsals, the fact of having been hired for, and successfully completed, a high-profile international production has already increased the level of respect and trust my students afford me in the classroom, allowing the training and instruction I provide to be more impactful. Students give greatest credence to their teachers in the classroom when they can observe their professional work directly, and/or by having evidence that their instructors are continuing to be professionally successful and sought after in the field they themselves are preparing to enter.

Reporting/Feedback from Colleagues:

Feedback from colleagues about the production, both solicited and unsolicited, was positive, and spoke not only to the final production played before audiences, but also to the friendly, inclusive, and positive environment I created which set the tone for the company’s work throughout the production process. Feedback was gathered through formal and informal dialogues with the persons listed below (please note, this list is not exhaustive and represents a sample).

Danial Nicolai (Artistic & Executive Director)

Igor Trulja (Marketing & Graphic Design Head)

Marc Francium (Casting Director)

Richard Evans (Scenic & Costume Designer) J

ohannes Volk (Lighting Designer)

David Gumpper (Sound Designer)

Henry Rehberg (Video & Projections Designer)

Maria Wending (Assistant to the Artistic & Executive Director)

Andrea Loenhardt (Head of Public Relations & Press)

Melanie Schöberl (Production Manager)

Leanne Maksin (Stage Manager)

P.J. Escobio (Theatre Pedagogue)

Gemma Brady (Assistant Stage Manager)

Elke Hermann (Deputy Stage Manager)

Dirk Conrad (Properties Master)

Maximilain Borschel (Sound Technician)

Mathias Lyssy, Damian Arkadiusz, Lucas Wentzel, Marcel Schmidt (Scenic Technicians)

Feedback commenting upon the positive atmosphere of the production process is particularly gratifying as creating and maintaining a production environment that is disciplined, productive, creatively satisfying, collegial, and allows people to do their very best work stems from the approach and tone set by the director: something I work actively to create and maintain.

The significance of these responses is doubly impactful when viewed with an awareness of the myriad challenges ETF had experienced since the onset of the COVID pandemic. ETF was hit incredibly hard by another challenge: two grueling years without a technical director. Lacking someone in this critical position meant the technical areas of the theatre and the employees therein had no oversight, direction, or advocate. Every person on the technical staff was on the ragged edge by the time The Totalitarians was scheduled to start, with several people in key areas ready to quit. It was communicated later to myself, the creative team, and the theatre management that the atmosphere of the production was the single deciding factor in several key employees staying in their jobs. It is worth noting that, as of this reporting, ETF has found a new Technical Director to oversee technical production duties.

Audience Response:

Production Stage Manager Leanne Maskin and Assistant Stage Manager Gemma Brady documented in regular performance reports that audience responses were consistently very good to excellent throughout the run of the production. There were no fewer than three curtains calls at any performance, as many as six curtain calls on many occasions, and standing ovations most weekend nights.

Press:

The Totalitarians was reviewed in five news / entertainment publications: Frankfurter Rundschau, Frankfurter Allgemeine, Frankfurter Neue Presse, Darmstädter Echo, and KultureFreak.de. There are brief excerpts below from each publication, respectively.

Frankfurter Rundschau

“As director Mineart correctly recognises, the play will inevitably be watched with Trump in mind, i.e. from the standpoint of a permanent crisis with the potential for many things, or in the extreme: constitutional crisis, revolution in the second attempt, a climate for attacks and civil war, presidential dictatorship, erosion of democracy in America, or an authoritarian form of government.

The Totalitarians illuminates an intermediate stage on this path. This is an extremely instructive piece of well-directed work.”

Frankfurter Allgemeine

“And you would be amused by the wonderfully exaggerated characters in Mark Mineart's deliberately boulevardesque production, if only reality had not long since replaced the caricature...this take on the situation is not that far removed from reality. And not only in the middle of America.”

Frankfurter Neue Presse

“Mark Mineart has produced the first performance of the play in Europe for the English Theatre Frankfurt. With energetic freshness and flashy allusions, a fabulous quartet of actors, absurd wit, and no hesitation about the sexual transgressions of the protagonists.”

Darmstädter Echo

“And as quickly and sharply as director Mark Mineart stages this satire at the English Theatre...the play that Peter Sinn Nachtrieb packs into the four characters and that the director then extracts with a wit that is as wicked as it is frivolous is highly entertaining. The play has bite and yet still comes across as light.”

KultureFreak.de

“The Totalitarians...directed by Mark Mineart, offers grandiose entertainment with a romantic and cynical touch...a sober view also into German everyday life, and the need, not only populist, to believe empty phrases.”

Peer Review:

It had been my intent to solicit a peer review from an American colleague who was scheduled to be vacationing in Europe during the time The Totalitarians was in performance. Their trip was, at the last minute, cancelled due to booking work on Broadway.

As per Section II, C of the Otterbein Department of Theatre & Dance Statement on Scholarship (approved by the University Personnel Committee June 2009),

“For off-campus work at a professional theatre or another university, the act of being hired shall be considered prima facie evidence of peer review. That is, a positive professional judgement of the quality of the faculty member’s prior work has been made...No Additional outside peer review is required.”

While not what had been initially intended as a metric of success, my hiring by English Theatre Frankfurt to direct The Totalitarians constitutes evidence of peer review in the eyes of our institution. I humbly submit this, as well as the other evidence of commercial, critical, and creative successes put forward previously in this report in lieu of a formal colleague’s review.

Goal 2: to actively learn from grappling with each of the challenges/opportunities outlined in the project description:

a.) to meet the challenges inherent in attempting to frame the events of the play as extreme against the backdrop of the American political landscape since 2015.

a.) The Totalitarians is a political satire that explores the destructive power of early 21st century American politics and language; how these things are being abused to control the American public to achieve power for power’s sake, as well examining the costs involved when political polarization destroys relationships, attacks social norms, and ultimately poses a threat to our democratic Republic. At first blush one could imagine The Totalitarians was written as a referendum on Donald Trump. However, The Totalitarians premiered at the Southern Repertory Theatre (New Orleans, LA) on Feb 1, 2014, 18 months before Trump declared his candidacy for President in June of 2015. The play drew much of its inspiration and influences from the politics and personalities of the 2008 presidential race, specifically Sarah Palin.

I took several actions to address the challenge of having the events of the play land with audiences as extreme when compared with the ludicrous heights of foolishness and folly that are so prevalent in American politics today. It was critical to be successful in this, for, without it, the machinery of the play could not produce its intended effect.

In the rehearsal hall, my work was to help guide the actors through the trajectory of their character arcs so that in performance audiences would experience Penny and Ben becoming ever-more extreme in their desires as the play moved forward. This was achieved by having the physical and vocal presentation of the characters, and how they are played, become more intensified and fanatical as the play unfolds. Stylistically, the world of the play is grounded in our contemporary reality, as are the characters and how they are acted. By the end of the play every action of Penny and Ben is larger, more intense, more fanatical and extreme, even to the point of farce. In contrast, the characters of Jeffrey and Francine were played realistically throughout the play, providing the necessary frame of reference through which the audience experiences the extremity of Penny and Ben’ fanaticism.

My work with scenic and costume designer Richard Evans was another avenue of attack: both scenically and through the costumes of two key characters: Penny (the political candidate) and Ben (the activist-cum-terrorist standing against her). Through the progression of these characters’ costumes - starting with small changes early on and progressing to ever larger ones as the play continues to unfold - we visually reinforced and intensified for audiences how extreme Penny and Ben become, supporting audiences viewing them almost as living personifications of their beliefs, goals, and grievances. To create a baseline against which these transformations could take place, the other two characters in the play, Francine and Jeffrey, as with their acting styles, remained more consistent, this time in their costume presentation, throughout the play.

Scenically, the physical environments where Penny or Ben was the dominant character (ex: Penny’s campaign office, Ben’s basement apartment) also shifted to reflect the ever-increasing extremism of their characters as the play progressed.

All of these elements together, Penny and Ben forking away from the realistic presentation of Francine and Jeffrey into progressively more extreme acting styles, the reflection of their transformations in costume evolution, and the increased influence of Penny and Ben on their dominant environments allowed us to point up the extremism of the events of the script and thereby achieve the goal of the play with our intended audiences where a ‘straight-realism’ approach would most likely have fallen short.

b.) ‘landing’ the play with predominantly non-native English speaking audiences in terms of language comprehension, as well as comprehension of American comic sensibilities.

b.) The voice of The Totalitarians is uniquely American in its expression, humour, and underlying identity. Most of the adult population of greater Frankfurt speaks very good English, specifically, British English. British English and humor also have a distinctly different feel and sensibility than American English and American humour. Familiarity with the workings of American politics was another aspect of production where our audiences would have little to no foothold.

These were the three primary barriers to successfully delivering the play to audiences of non-native English speakers: context, clarity, and comedy.

Context:

When European nationals think of the USA, Nebraska is not what leaps to mind. Unlike NYC, Las Vegas, or Hollywood, Europeans, writ large, possess no knowledge, or even preconceptions, about what Nebraska and life in Nebraska is like. That was something we were going to have to provide our audiences at the outset in order for the production to succeed. This was attacked using music, projections, and video. Some elements used were specific to Nebraska and aspects of the play, other media were chosen to create a useful idea of Nebraska and a feel for rural America more generally.

For Pre-show, Interval, and Post-show audio I selected music that would create a trope- ish feel of rural America that mirrors, roughly, how coastal and metropolitan Americans imagine ‘fly-over country’ (ex: Big Sky by The Wild Feathers, Crushin’ It by Brad Paisley, Where the Stars and Stripes and the Eagle Fly by Aaron Tippen) along with some pieces that spoke specifically to Nebraska culture, specifics of the play and its characters (ex: The Cornhusker by Killigans, Roller Derby Queen by Jim Croce, Christ for President by Billy Bragg & Wilco).

To create a context for the audience of the physical environmental of Nebraska outside the physical scenery on stage I selected still images of different locations in Nebraska that spoke to the character of the state (ex: corn fields - the primary agricultural crop, Cornhusker fans at a football game, Car-Henge - one of the landmarks of the state, etc). These images were shown on a large rear-projection screen that was integrated into the scenic design during the Pre-show and Interval.

As a final element for setting the context of the play for the audience I found a series of pro- tourism videos the Nebraska Tourism Commission had produced. these were shown at the end of the Pre-show and Interval as the lights were going down to kick off each act. I was particularly fortunate to have dug up these videos in my pre-production work. These videos spoke with Nebraska’s own voice about the state and how they wanted people outside of Nebraska to view their home, as well as providing an invitation to visit:

Based upon the reception of the production by audiences, the press, and the success for ETF, my efforts to create a context within which the play could be appropriately received was a success.

Clarity:

The setting of the play required actors to take on a ‘Nebraska’ dialect. There are a variety of different American dialects found in Nebraska depending upon where you are in the state: Western North English, Western English, Midland English, and North Midland English to name those predominant in the state. Most of the events of the play are located in an area where North Midland English was spoken, and i selected that as a basis for the dialect to be used in performance. All of the actors had demonstrated a Standard American dialect in their audition videos similar to the type of sound you here in the average American TV series and I was confident in their ability to meet the dialect needs of the show.

The majority of dialect work was not in teaching the dialect itself, but rather balancing the thickness of the dialect and softness of articulation for German ears. When Germans hear English, they predominantly hear it spoken with a British dialect. My goal with our dialect was not to achieve a clinical accuracy, it was to create a sound to the spoken English of the play that would evoke the feeling of middle America while at the same time being easily receivable by our audiences. I settled on a modified set of sound changes: some eliminated, others toned-down for clarity. This produced a pleasant, clearly Breadbasket American sound distinct from other major American dialects (ex: New York, Boston, etc).

Hallmarks of British English are that it is clear, clean, fully articulated, frontally placed, and therefore extraordinarily easy to receive and understand. Also, because of the sentence construction, vocabulary, and rhythm of American English generally and the Midland North English dialect specifically, in addition to the fact that theatrical comedy needs to be played a reasonable clip, to have incorporated any articulatory softening of speech would have caused audiences to miss too much of the text to remain with the narrative.

Comedy:

The Totalitarians, is, at it’s heart, a situation comedy, and makes use of physical, contextual, and the spoken word for its humour. Physical comedy is almost universally portable, and contextual comedy can land even if only the broadest understanding of the situation is understood. I was not overly concerned about being able to deliver these comic elements of the play. But spoken word comedy is a different beast and does not always translate. For example, The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson was beloved in America and left Brits bored when it was first broadcast across the pond. More recently, Raymond Teller (of Penn & Teller) said in an interview, “'Here in England, I think I've still got the best job. My silent reactions and takes are more universally understood than dialogue.” Simply put, though there is a great deal of crossover, American and British comic sensibilities and tastes are not the same.

Another challenge for the production was that much of the play requires some knowledge and understanding of American politics in order for some of the humour to land. To Nachtrieb’s credit, a general understanding of how American elections and governance work is sufficient. But, would that be too much to expect of our Frankfurter audiences?

Diving into educating the cast on the mechanics of American politics went a long way to overcoming any knowledge barrier on the part of audiences. The actors were eager for the information and used it to successfully serve up the political elements of the play in such a way that was not only clarifying for audiences, but engaging.

In examining other comic elements of the play it became clear: some things would clearly translate to German audiences, others would work with a bit of help: a particular bit of timing, a gesture or a look, etc). There were other jokes where it was impossible to predict if they’d work until they were actually presented in front of dress run audiences. And, finally, there were a very small number of gags that seemed impossible to make go, no matter how they were executed. Example: Penny (candidate) and Francine (campaign manager) find out that Penny’s chief political rival for the Lt. Governorship committed suicide, naked, in a hob tub at an oriental ‘spa.’ The dialogue immediately following their receiving the news goes as follows:

“Penny: Well, well, well.

Francine: I had no idea he...

Penny: In that location.

Francine: So close to the election.

Penny: Seemed so put together.

Francine: And the polls were still close. What a weird time to...

(penny makes a throat cutting suicide gesture) Penny: Oh, October.”

‘Oh, October,’ is the punch line of the joke. It’s a good joke, but not a guaranteed laugh with our non-native English-speaking audience demographic in Frankfurt.

The line references an ‘October Surprise.’ This is a term given to an unexpected political news revelation in the month before a November election that could potentially turn the tide of a race. We worked the line throughout the rehearsal period trying a variety of different takes and deliveries. We tried it out in previews, but, unsurprisingly, it never landed with audiences. In this instance, however, missing the laugh wasn’t the biggest problem with the line.

Because the audience didn’t know the term the line was referencing, the line not only failed to get the laugh, it hooked the audience’s attention. They were stuck wondering what was that?, did I hear that right?, was that a joke?, and all the while the play was moving forward and the audience wasn’t just confused, they were behind the narrative and in danger of losing the plot.

After final dress I cut the line and directed Penny to go with business we had developed in rehearsal, knowing that we were likely to cut the line in the end. this was the business: right after the suicide gesture, Penny would give a look that only the audience would see that showed her secret delight at her opponent’s death. We got a laugh where the play was wanting one for the sake of momentum, and the audience didn’t get pulled out of the narrative.

Takeaways:

Meeting these challenges has provided greater insight in how to approach content for unfamiliar audiences. I have also gained a greater clarity into the differences in the particulars of American vs UK vocabulary and slang, thought construction, acting approaches and styles, differences in the comic sensibilities of the US, UK, and Germany, as well as learning how to better communicate with, direct, and guide partners who, though we all come from a ’western’ environment and, in some cases, share a common language, inhabit different professional and artistic milieux.

c.) casting, coaching, and directing an entire company of UK natives in a convincing, and easily understandable Mid - American dialect, as well as in the complexities of American comic sensibilities, timing, and tone.

Casting:

Casting The Totalitarians represented several firsts in my experience. English Theatre Frankfurt casts native English speakers almost exclusively out of London. Initially the plan had been to fly me to London for a week to do preliminary as well as callback auditions. Having experienced UK casting practices when auditioning for my first Broadway show with a prominent Welsh director, I was eager to experience that process from the other side of the table on The Totalitarians.

However, technical delays on ETF’s production of Young Frankenstein, as well as a COVID outbreak amongst the cast pushed back the entire production timeline, necessitating casting be done from video submissions. I’ve cast this way before and while it works, it is not ideal. In a video submission the acting tends to fit the size of the video frame, which produces auditions that are rather filmic rather than theatrical, which is what is wanted, naturally, when casting for live performance. however, being theatrical on video submissions tends to look overblown and false because we are so accustomed to the acting scale predominant on the small screen.

The major problem with video auditions in my view is that I do not get to actually meet the actors. For me this is a critical component of casting. If I’m seeing an actor for a professional production I take it as read that they’re talented and capable, otherwise they wouldn’t have gotten in the room. Acting-wise the question is whether or not they’re a good fit in the show. I can get all that from a video. What I can’t get from a video is what the auditionees are like as people. What I really need to know is whether we’ll get on together when we are pulling lots of long hours six days a week working on a show. Can they take a note and make adjustments, will they do their work, are they relaxed, interesting, do they seem like a good person? The three most important things to me when casting any actor are, in order:

1. Easy to work with and drama free

2. Always prepared

3. They do the job

In collaborating with Marc Franckum, ETF’s casting partner in the UK, I related to him what I was looking for for each of the characters and I was much reassured in that he understood my preferences and seemed very much on the same page in regards to the actors he brought in for auditions.

Marc sent out a character breakdown to various talent agencies and managers in the UK requesting submissions. He then reviewed those submissions and selected a number of candidates for each role in the show for my consideration.

Marc had done really well and given me a nice variety of actors who made strong, smart choices about their characters, as well as a nice span of ages and physical to consider. There was one clear choice for one of the more difficult roles and for others I asked Marc to go back to a select number of actors and request another take on the material based on notes I provided. After viewing those videos and narrowing down my selection possibilities to one or two actors per role I discussed each actor I was seriously considering with Marc. He was very helpful and shared his experiences with, and knowledge of, each of them in the past. Marc did a fabulous job for me and I was fortunate enough to get all of my first choices in every role.

There are a small number of American actors living in London, and while I had been quite keen to get at least one Yank into the company as a resource, the cast of The Totalitarians was comprised exclusively of three Brits and one Scot. This meant that a non-trivial amount of rehearsal time would be needed to prime the performers on how to address the required dialect, the uniquely American aspects of the play, and other challenges we faced in our pursuit.

Coaching:

The setting required actors had to take on a North Midland American dialect. All of the actors had demonstrated a Standard American dialect in their audition videos and I was confident of their abilities. This topic was addressed in detail in Goal 2, Clarity. Please see that section for more detail.

Setting the Tone:

It is very important to me to create a highly collegial professional atmosphere where everyone can feel at ease, respected, valued, supported by the director, and given the opportunity to do their very best work. That environment comes from the director. Two of the most impotent things a director must do to set a production up for success is to cast well, and create an inviting space for the work. I had the benefit of learning this lesson at the hands of Ed Stern, former Artistic Director of the Cincinnati Playhouse. The production atmosphere includes the environment for designers, the technical staff, the stage management team, the running crew, literally everyone needs to know that they are important, that their work is necessary, valued, and respected.

Directing:

Working with the actors from the UK was a wonderful experience. It was a great opportunity to compare and contrast their ways of working to my own, as well as with methods generally seen as standard practice in the American professional theatre.

It was also refreshing and illuminating to be working with a professional company of performers again. This reinforced to me areas where we are serving our students incredibly well in their training, and highlighted others where our students are not meeting, or, more accurately, are not capable of receiving the training necessary in order to be able to meet outcomes of training that are critically necessary for success in the profession. These are not shortcomings of the faculty, these are well-documented, continuing, alarming concerns pervasive at the national level. Colleagues of mine teaching in BFA and MFA programs both in Ohio and across the country are experiencing the same concerns.

Sadly, these concerns are no longer confined to the United States. Both my UK and German colleagues shared that the fragility, the lack of resilience, an almost belligerent entitlement, and the seemingly compulsive need to take offense, construe harm, and assign blame are beginning to be found in their countries as well, though not yet nearly as severely or pervasively as in the States.

At the end of week one on The Totalitarians I realized that I had been conducting myself in rehearsals as I often feel the need to do at school as a means of self- preservation: walking on eggshells, couching notes in effusive praise, not giving the tough note straight out, being over-accommodating in looking for consensus on decisions that are solely mine, approval-seeking, and all for fear of upsetting or offending someone, or worse yet, being called-out for some perceived offense where none was intended. This isn’t who I wanted to be on the project and so i set out to change it.

“The play’s the thing!” became my mantra. The quality and pace of the work increased and there was a greater atmosphere of ease and purpose in rehearsals going forward. Interestingly, my interactions and work with the technical areas of the production never suffered from what I experienced with the performers in the hall in that first week. I think that because all of the various technical areas produce artifacts that are mutually observable simultaneously by the the creator and the director. The footprint of a custom built desk, for instance, is something that can be taped out and measured and both parties can step back and regard it. That is not the case when evaluating the work of a performer. The work of the performer cannot be objectively observed because it exists only moment to moment and it’s mechanism of delivery is the actor’s body. Only the director can observe it from the outside. Discussion of the performer’s craft is therefore intrinsically more difficult to discuss, and likely to taken more personally, and therefore I, as a director who is also an actor, have a sensitivity when giving performers notes.

There was a breadth of experience, skills, and acting approaches amongst the company of The Totalitarians, which enriched the experience of working with them. There were also aspects to their work that they had in common which differ from actors in the states.

They memorized faster. Most of the actors were fully memorized when they arrived at the first rehearsal. All of them were at least partially memorized. In the States it is much rarer to see actors fully off script when they walk in the door.

They worked slower. I think this may be because in the UK there are generally more weeks of rehearsal. In the States it is not unusual to have 3 weeks of rehearsal and one week for tech and dress rehearsals combined. Because of this I tend to stage quite quickly, usually an act per week of rehearsal. I then use the remaining rehearsal days to work through the each act sequentially scene by scene making adjustments and adding detail running each act after finishing. The last few days of rehearsal are run throughs with notes following. because of the tightness of the American schedule I take advantage of tech rehearsals (where there is a lot of stop and start for scenery, costumes, lights, sound, and sfx) to give acting notes and adjust staging now that the production is actually on the set.

My plan of attack and pace caused some discomfort for the UK performers who, being accustomed to having more time to explore staging and relationships and moment to moment beats at greater leisure in the early weeks of rehearsal, were concerned about getting locked into staging before they had fully tracked the internal journey of the characters through the play. Once expressed, I happily adjusted the schedule to allow more time for working through the play slowly, and pushed back run-throughs until quite late in the process.

They played smaller. This downright shocked me. One of the things I have long admired and worked to emulate is the ability of UK actors to work successfully both on the screen and on the stage. They are far more skilled at this than we Americans are, in no small part because the largest theatre market in the UK and the largest screen market in the UK are both in London, whereas in the US they are literally a continent apart.

Eliciting more theatrical performances what not sometime I had ever imagined needing to do with my UK actors, but it ended up being part and parcel of the work. Four pieces of direction paid the greatest dividends in getting the theatricality and energy needed from the performers. I instructed them to think of the style of the play not as satire, but as sitcom. Secondly, I asked them to let each moment be what it is and to resist any urge to reconcile them with one another. When actors do this it flattens out the peaks and valleys of the plays dynamic range and reduces it to gently rolling hills. The third was to eliminate transitional moments between dramatic beats (except where specified in the text); in other words, listen, breathe, speak. Finally, every time they get to speak, put new energy/intention into the situation in the same way that a tennis racket imparts energy and momentum when it contacts the ball.

They were dedicated and generous. A frustration in the American professional theatre, and at Otterbein, is complaints about rehearsal calls. Actors complain about not booking work, and then when they do, they complain about having to be in rehearsal.

On The Totalitarians it had been my full intent to break down the actor calls so that, as much as possible, no actor would have to spend a lot of time waiting around during the course of their work day. Well, I scheduled that way for about a week. Then the actors suggested that rather than trying to work out all the blocks of time, why not just call them all for the entirety of every rehearsal day? That way a scene could take the time it needed to take rather than getting short shrift, and if a scene ended early than expected, the next scene could start right away.

I could have hugged each and every one of them. This is the way I was brought up in the theatre too. If I was on a job, then those rehearsal hours belonged to the production and not to me. Also, if i don’t know the whole play intimately then how can I possibly know how to do my work for the plays greatest benefit?

They were no nonsense. There were several sequences of stage combat in the play: two contact slaps, a from-behind choke with an associated drag, a groin grab/twist, and the attack and stabbing to death of someone from behind with an arrow. There were two instances of a firearm being discharged on stage (backstage blank gun), as well as a practical arrow being shot from on stage to off stage (catch-and-keep barrier).

There were also three sequences that required theatrical intimacy in the play. Two of these scenes were consenting couples kissing and then moving to a bed where they begin undressing and starting to make love. The last sequence was also consensual, though one-sided: a husband touching his wife’s mid-thigh and kissing her neck, trying, unsuccessfully, to get her interested in intercourse.

There was once instance of nudity in the show, a man’s buttocks.

Throughout all of this work, the actors were nothing but professional. I teach stage combat and therefore able to take on the responsibilities of fight director. ETF offered to hire an Intimacy director to create the choreography of the three sequences of physical contact. In a blind vote (to which I, or course, was not a party) the actors unanimously voted to do their own intimacy choreo. Those rehearsals would be closed - only the participants and stage manager in the room. The choreography would be demonstrated for my review and feedback. Any adjustments would be handled in the same manner as initial choreography.

Intimacy on stage and screen is a big issue in the States and not without good reason. Unlike dance choreography and fight direction - where an appropriate expert is hired for that work - sequences of intimacy on stage screen didn’t have a codified approach to the work. With the #MeToo movement abuses in stage/screen intimacy began coming to the fore. Intimacy direction as a discrete discipline has been growing, particularly in screen work where sequences of apparent intimacy tend to be more explicit. Being safe and specific when creating apparent intimacy on stage is vital.

The sanguine and professional attitude all of the cast took toward the intimacy and nudity was impressive, mature, and reassuring. It was clear that they, and I, knew their voices were the ones foremost in that work, that they would not be asked to do anything that made them feel at risk, and that they were in circumstances were they were safe, respected, and could communicate without fear.

The instance of nudity was suggested by the performer himself in rehearsal.

The company took the same attitude to all of the stage combat work, though that choreography was created by me in conjunction with the actors involved, as well as the sequences involving firearms and the bow and arrow.

Goal 3.) to model American professional best practices throughout the entire process of production; from pre- production, casting, rehearsals, technical rehearsals, opening, and closing.

Modeling American professional best theatrical practices throughout the process was, in almost all instances, useful and educational, though not always possible due to a variety of factors. With three different expressions of best practices, American, United Kingdom, and German, there was common ground, opportunities to raise the bar, as well as opportunities to learn by example and from failure.

Within the rehearsal hall, we were highly successful in synthesizing American and UK best practices. By unanimous agreement we ran rehearsals based upon a modified straight-six schedule: three hours of rehearsal, thirty-minute break, three hours of rehearsal, end of day. The atmosphere in the hall was consistently congenial, relaxed, and enjoyable, and everyone on the team contributed directly and greatly to the production.

Outside of the rehearsal hall, however, it was a much different story. As communicated previously, ETF had been operating under extraordinary circumstances for close to two years. Whereas rehearsal were humming along the absence of a Technical Director mean that there was no point person to manage the various areas of technical production: scenery, costumes, props, lights, sound, and sfx. Without this critical oversight each area was required to fend for themselves, working as best they could to get everything done despite there being no larger plan.

The Totalitarians was a big and complicated for ETF both in terms of building and running, particularly as the last show of the season and everyone was on last legs and things were already behind schedule due to prior delays in the season and COVID. Moral was incredibly low when I arrived in Germany.

To give some scope of the task: the set itself was two stories high, included a revolve, two synced projectors throwing images and video (some pre-recorded, most on a live feed a video camera on the stage itself) onto a rear projection screen. There was a front projector as well as confetti canons and a coordinated banner and balloon drop (the balloons were over the audience which required additional rigging)in the final scenes with much of the sfx happening simultaneously. Additionally there off stage live- gunshots as well as the firing of a practical arrow from in the stage into the wings for which a protective ‘catch and keep’ barrier had to be created, as well as trick pop-up arrow build into a desk.

I took several approaches to helping as best I could. Chiefly, I made myself as available to all of the areas as much as possible, during breaks, before and after rehearsals and before and after production meetings. I made it a point to visit the various shops on a regular basis, talking to the designers and artisans whenever it was not an interruption for them. My training involved working in all aspects of theatre-making and I’ve always enjoyed working in the shops and backstage. Most directors don’t visit the people or shops building their shows, which I think is a grave mistake, not to mention disrespectful.

I actively sought to eliminate problems before they began by staying abreast of what difficult or crucial builds were taking place and getting into the shops prior to construction to confirm designs and clarify specifics. In conversation with my designers I actively sought to reduce and simplify area work loads whenever possible (cutting props, simplifying scenic elements, choosing the best of available options for a costume piece rather than demanding something be built) so the build teams could spend their limited hours and resources on things that would provide the greatest benefit to the production.

And finally, and perhaps most importantly, I learned everyone’s name in every area, got my own hands dirty where I could (specifically image shooting and editing for projections and audio cue recording), and said ‘thank you’ a lot.

One of the greatest satisfactions on my entire sabbatical was seeing the alteration in the mood and morale of the ETF staff between the beginning of the production process and opening night

Goal 4.) to refresh and increase my knowledge of the current European, specifically, German & UK, theatre aesthetic, practices, and environment, where these elements currently stand, what is influencing them, and perhaps gain insight, certainly perspective, on how they compare to current trends in the American theatre as well as how they relating to the Diversity, Inclusion and Equity movement happening in the American theatre.

Comparing and contrasting German and United Kingdom theatre attitudes, environments, and aesthetics with those of the American theatre was, while not revelatory on a grand scale due to prior experience and research, still highly illuminating.

The greatest aesthetic overlap exists between the US and the UK in terms of the type of material each creates and produces, as well as the general styles and manners of production. Where the US and the UK differ greatly, however, is in the breadth of offerings available to, and frequented by, UK theatre-goers, which is vastly more diverse and balanced than our theatrical menu in the States. Restoration Comedy, for example, is rarely done in America except very occasionally at classical theatre festivals, and even there, rarely. Classics and other challenging works (Pinter, Beckett, Moliere) are found regularly upon the stages of the UK, and only venture to the states if the production is a huge in in London.

The German theatrical palette is even more varied that of the UK in the breadth of its offerings, and broader still in its aesthetics and manners of production. Classic works regularly get turned on their heads and blur the lines between traditional theatre production and performance art. Quite distinct from the theatre aesthetics of the US or UK that tend to follow a linear, climactic path, in Germany you might encounter a very traditional Faust one night and then experience a piece of that may have only one line of text in the entirety of a two hour performance. German theatre exists more as an artist’s medium than a performer’s and is as much about provocation and experimentation as it is entertainment, perhaps moreso.

The major differences in professional approach and practices were those between the American/UK and German ways of working and of thinking about work (specifically those at English Theatre Frankfurt). The ETF receives no state support. Additionally, the theatre is not a member of the Deutscher Bühnenverein, the German theatre union, nor are the majority, if any, of its employees. These differences contribute greatly to the manner in which it functions.

Many political, social, and ethical issues are major concerns in America. These are also concerns in the UK and Germany, but they manifest themselves very differently than they do in the States, both in society and in the theatre.

The concerns surrounding representation and inclusion, workplace safety, discrimination, unconscious bias all exist, but the conversations around them are of a different character. Largely absent are the fear, anger, fanaticism, and extremism that is part of our current American gestalt.

The people I worked with, socialized with, encountered, were thoughtful and reasoned, open to constructive exchange through discourse, willing to be legitimately brought to a different point of view for the good of the whole. The cumulative result was a less fraught (no fear of being called-out, or cancelled, or labeled as an its of any kind), yet more challenging (in the best way), more productive, congenial, and enjoyable space within which to work.

Post-Sabbatical Notes:

I am extraordinarily grateful for the opportunity to take this sabbatical and for the tremendous opportunities for growth and experience I was able to take advantage of in all areas of my professional practice as a theatre-maker, and as a teacher and coach. Since coming back to Otterbein in Spring 2023, I have begin incorporating some of the things I learned and observed during my sabbatical into my classroom teaching, rehearsal process, and in larger conversations at the departmental level concerning curriculum, practices, and policy. There is a tremendous lot for me still to process, but even now, I am seeing the larger, less tangible influences and lessons from my experiences coming through in my teaching and interactions with students.

Reflecting upon the work of my sabbatical over the months since returning to the US, and in preparing this report, I had a realization: I assert one of the primary reasons The Totalitarians achieved such a level of success, even in the face of numerous significant obstacles, was because I made more mistakes. And I made more mistakes because where I was, the environment I was in, the people I was with, provided me the room - without fear - to make those mistakes, and because of that room, I benefitted from the mistakes rather than condemning myself, or living in dread of the consequences, for making them.

I have not found that space, or generosity, in the United States since my return, and in recognizing that, I also realized that it has been missing here for quite some time.

- Mark Mineart